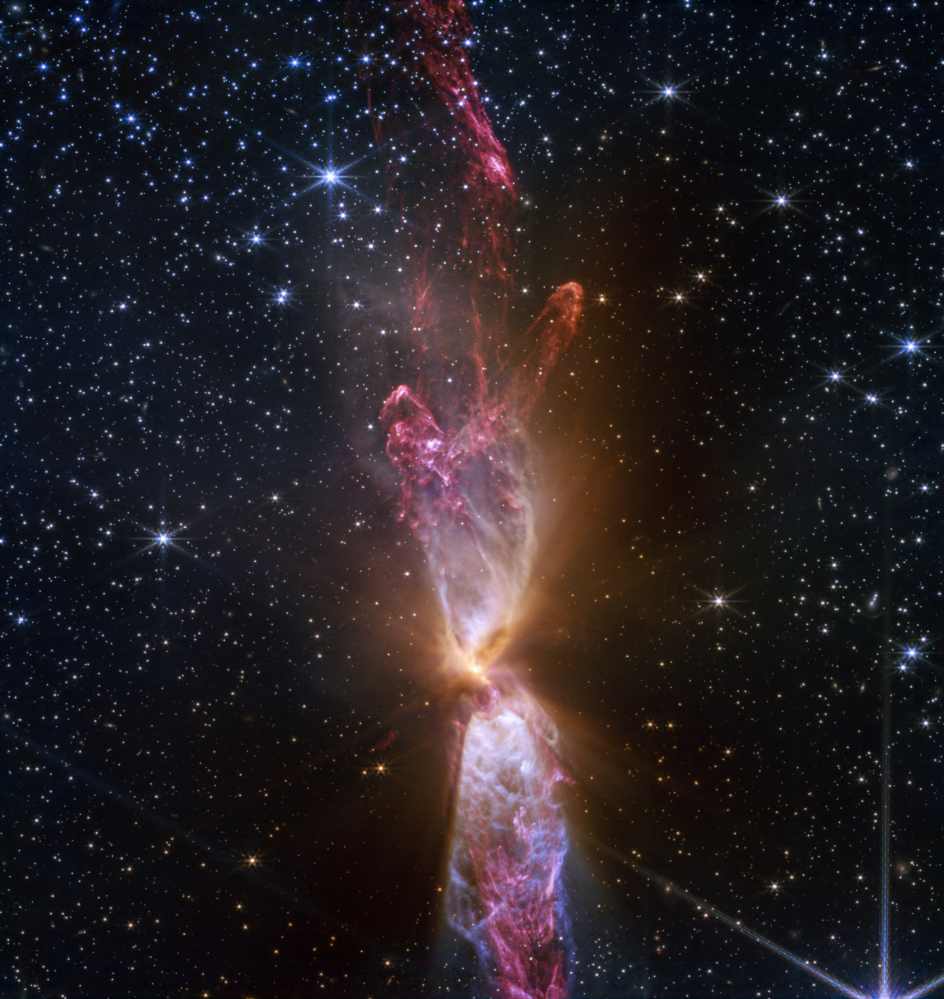

The high-resolution near-infrared light captured by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope has unveiled remarkable new details in Lynds 483 (L483). The image showcases two actively forming stars responsible for the stunning ejections of gas and dust that shimmer in orange, blue, and purple hues.

Ejections and Their Impact

Over tens of thousands of years, the central protostars have intermittently ejected gas and dust, creating tight, fast jets and slightly slower outflows that travel through space. When newer ejections collide with older ones, the resulting interactions cause the material to crumple and twirl based on their densities.

Chemical reactions within these ejections and the surrounding cloud have produced a variety of molecules, including carbon monoxide, methanol, and other organic compounds.

The Hourglass Structure

The two protostars at the center of the hourglass shape reside in an opaque horizontal disk of cold gas and dust. Above and below this disk, where the dust is thinner, bright light from the stars shines through, forming large semi-transparent orange cones.

Dark, wide V-shaped areas offset by 90 degrees from the orange cones indicate regions where the surrounding dust is densest, blocking most of the starlight. In these areas, Webb’s NIRCam has detected distant stars as muted orange pinpoints. Where the view is unobstructed by dust, stars shine brightly in white and blue.

Twisted and Warped Jets

Some jets and outflows from the stars have become twisted or warped. For example, a prominent orange arc at the top right edge of the image marks a shock front where the stars’ ejections were slowed by denser material. Lower down, where orange meets pink, the tangled appearance of the material reveals incredibly fine details that require further study.

In the lower half of the image, thicker gas and dust are visible. Zooming in reveals tiny light purple pillars pointing toward the central stars. These pillars remain because the dense material within them has not yet been blown away.

Future Implications

All the symmetries and asymmetries in these clouds may eventually be explained as researchers reconstruct the history of the stars’ ejections. By updating models, astronomers aim to produce similar effects and calculate the amount of material expelled, the molecules created during collisions, and the density of each area.

Millions of years from now, when the stars finish forming, they may each be about the mass of our sun. Their outflows will have cleared the area, leaving behind a tiny disk of gas and dust where planets might eventually form.

Honoring Beverly T. Lynds

L483 is named after American astronomer Beverly T. Lynds, who published extensive catalogues of “dark” and “bright” nebulae in the early 1960s. By examining photographic plates from the first Palomar Observatory Sky Survey, Lynds accurately recorded each object’s coordinates and characteristics. These catalogues provided astronomers with detailed maps of dense dust clouds where stars form, serving as critical resources for the astronomical community.

Provided by European Space Agency