There’s a hot new BEC in town that has nothing to do with bacon, egg, and cheese. You won’t find it at your local bodega, but in the coldest place in New York: the lab of Columbia physicist Sebastian Will, whose experimental group specializes in pushing atoms and molecules to temperatures just fractions of a degree above absolute zero.

Writing in Nature, the Will lab, supported by theoretical collaborator Tijs Karman at Radboud University in the Netherlands, has successfully created a unique quantum state of matter called a Bose-Einstein Condensate (BEC) out of molecules.

Their BEC, cooled to just five nanoKelvin, or about -459.66 °F, and stable for a strikingly long two seconds, is made from sodium-cesium molecules. Like water molecules, these molecules are polar, meaning they carry both a positive and a negative charge. The imbalanced distribution of electric charge facilitates the long-range interactions that make for the most interesting physics, noted Will.

Research the Will lab is excited to pursue with their molecular BECs includes exploring a number of different quantum phenomena, including new types of superfluidity, a state of matter that flows without experiencing any friction. They also hope to turn their BECs into simulators that can recreate the enigmatic quantum properties of more complex materials, like solid crystals.

“Molecular Bose-Einstein condensates open up whole new areas of research, from understanding truly fundamental physics to advancing powerful quantum simulations,” he said. “This is an exciting achievement, but it’s really just the beginning.”

It’s a dream come true for the Will lab and one that’s been decades in the making for the larger ultracold research community.

Ultracold Molecules, a Century in the Making

The science of BECs goes back a century to physicists Satyendra Nath Bose and Albert Einstein. In a series of papers published in 1924 and 1925, they predicted that a group of particles cooled to a near standstill would coalesce into a single, larger superentity with shared properties and behaviors dictated by the laws of quantum mechanics. If BECs could be created, they would offer researchers an enticing platform to explore quantum mechanics at a more tractable scale than individual atoms or molecules.

It took about 70 years from those first theoretical predictions, but the first atomic BECs were created in 1995. The achievement was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2001, just around the time Will was getting his start in physics at the University of Mainz in Germany. Labs now routinely make atomic BECs from several different types of atoms. These BECs have expanded our understanding of concepts such as the wave nature of matter and superfluids and led to the development of technologies such as quantum gas microscopes and quantum simulators, to name a few.

But atoms are, in the grand scheme of things, relatively simple. They are round objects and usually do not feature interactions that may arise from polarity. Since the first atomic BECs were realized, scientists have wanted to create more complicated versions made from molecules. But even simple diatomic molecules made of two atoms of different elements bonded together had proved tricky to cool below the temperature needed to form a proper BEC.

The first breakthrough came in 2008 when Deborah Jin and Jun Ye, physicists at JILA in Boulder, Colorado, cooled a gas of potassium-rubidium molecules down to about 350 nanoKelvin. Such ultracold molecules have proved useful to perform quantum simulations and to study molecular collisions and quantum chemistry in recent years, but to cross the BEC threshold, even lower temperatures were needed.

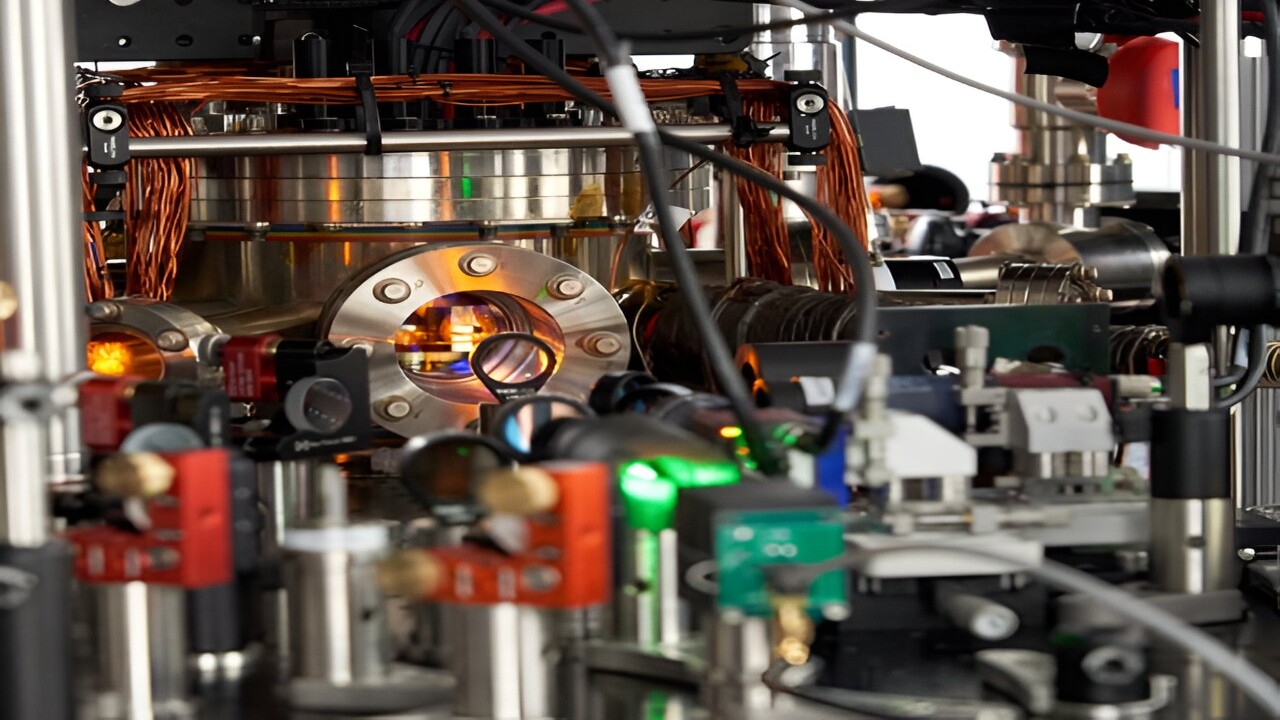

In 2023, the Will lab created the first ultracold gas of their molecule of choice, sodium-cesium, using a combination of laser cooling and magnetic manipulations, similar to Jin and Ye’s approach. To go colder, they brought in microwaves.

To Go Colder, Add Microwaves

Microwaves are a form of electromagnetic radiation with a long history at Columbia. In the 1930s, physicist Isidor Isaac Rabi, who would go on to the Nobel Prize in Physics, did pioneering work on microwaves that led to the development of airborne radar systems. “Rabi was one of the first to control the quantum states of molecules and was a pioneer of microwave research,” said Will. “Our work follows in that 90-year-long tradition.”

While you may be familiar with the role of microwaves in heating up your food, it turns out they can also facilitate cooling. Individual molecules have a tendency to bump into each other and will, as a result, form bigger complexes that disappear from the samples. Microwaves can create small shields around each molecule that prevent them from colliding, an idea proposed by Karman, their collaborator in the Netherlands. With the molecules shielded against lossy collisions, only the hottest ones can be preferentially removed from the sample—the same physics principle that cools your cup of coffee when you blow along the top of it, explained author Niccolò Bigagli. Those molecules that remain will be cooler, and the overall temperature of the sample will drop.

The team came close to creating molecular BEC last fall in work published in Nature Physics that introduced the microwave shielding method. But another experimental twist was necessary. When they added a second microwave field, cooling became even more efficient and sodium-cesium finally crossed the BEC threshold—a goal the Will lab had harbored since it opened at Columbia in 2018.

“This was fantastic closure for me,” said Bigagli, who graduated with his PhD in physics this spring and was a founding lab member. “We went from not having a lab set up yet to these fantastic results.”

In addition to reducing collisions, the second microwave field can also manipulate the molecules’ orientation. That in turn is a means to control how they interact, which the lab is currently exploring. “By controlling these dipolar interactions, we hope to create new quantum states and phases of matter,” said co-author and Columbia postdoc Ian Stevenson.

A New World for Quantum Physics Opens

Ye, a pioneer of ultracold science based in Boulder, considers the results a beautiful piece of science. “The work will have important impacts on a number of scientific fields, including the study of quantum chemistry and exploration of strongly correlated quantum materials,” he commented. “Will’s experiment features precise control of molecular interactions to steer the system toward a desired outcome—a marvelous achievement in quantum control technology.”

The Columbia team, meanwhile, is excited to have a theoretical description of interactions between molecules that have been validated experimentally. “We really have a good idea of the interactions in this system, which is also critical for the next steps, like exploring dipolar many-body physics,” said Karman. “We’ve come up with schemes to control interactions, tested these in theory, and implemented them in the experiment. It’s been really an amazing experience to see these ideas for microwave ‘shielding’ being realized in the lab.”

There are dozens of theoretical predictions that can now be tested experimentally with the molecular BECs, which co-first author and PhD student Siwei Zhang noted, are quite stable. Most ultracold experiments take place within a second—some as short as a few milliseconds—but the lab’s molecular BECs last upwards of two seconds. “That will really let us investigate open questions in quantum physics,” he said.

One idea is to create artificial crystals with the BECs trapped in an optical lattice made from lasers. This would enable powerful quantum simulations that mimic the interactions in natural crystals, noted Will, which is a focus area of condensed matter physics. Quantum simulators are routinely made with atoms, but atoms have short-range interactions—they practically have to be on top of one another—which limits how well they can model more complicated materials. “The molecular BEC will introduce more flavor,” said Will.

That includes dimensionality, said co-first author and PhD student Weijun Yuan. “We would like to use the BECs in a 2D system. When you go from three dimensions to two, you can always expect new physics to emerge,” he said. 2D materials are a major area of research at Columbia; having a model system made of molecular BECs could help Will and his condensed matter colleagues explore quantum phenomena including superconductivity, superfluidity, and more.

“It seems like a whole new world of possibilities is opening up,” Will said.

Reference: Bigagli, N., Yuan, W., Zhang, S. et al. Observation of Bose–Einstein condensation of dipolar molecules. Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07492-z