In August of the previous year, astrophysicist Dale Kocevski published a paper on the arXiv preprint server containing preliminary data on the discoveries made by the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) concerning black holes in a Universe survey. Although the article has now undergone formal review and publication, it did not anticipate the revolutionary insights that JWST would bring regarding these mysterious celestial objects. Kocevski, based at Colby College in Waterville, Maine, admits, “And that was proven completely wrong.”

Shortly after the publication, a flood of new research emerged. In September, one preprint surfaced, followed by numerous others in recent months, all revealing the existence of far more black holes in the distant Universe than astronomers had ever imagined. As of today, another dozen newly discovered black holes have been reported in a preprint. JWST’s unparalleled power has enabled it to explore an extensive range of black holes, from faint and distant ones to a select few bright ones residing even farther away.

Rebecca Larson, an astrophysicist at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, emphasizes, “It’s truly studying parts of the Universe that just weren’t available to us technologically.”

JWST’s research on black holes is still in its early stages, and astronomers caution that much remains to be resolved. However, it is already evident that the telescope’s discoveries have the potential to answer many long-standing questions about black holes, such as their formation in the early history of the Universe and their rapid growth into cosmic vacuums, devouring everything in their vicinity.

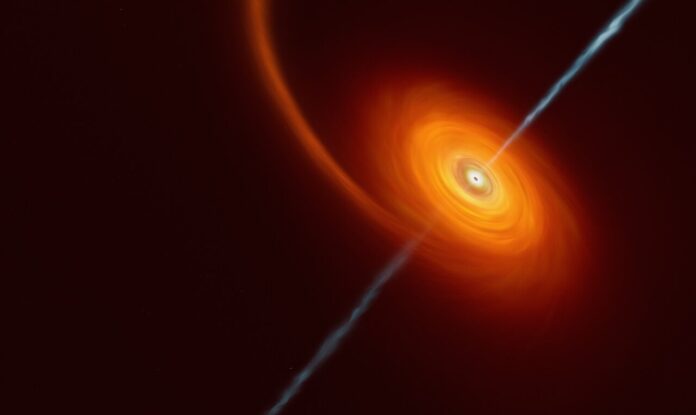

While black holes come in various sizes, JWST has primarily detected massive ones, weighing millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun. The exact process of how these black holes form remains uncertain, but it may involve the collapse of massive stars or gas clouds, followed by the accretion of nearby gas and dust. In this scenario, these black-hole ‘seeds’ would grow rapidly until they become gravitational powerhouses lurking at the centers of most galaxies.

While black holes themselves are invisible due to their immense gravitational pull that even light cannot escape, they can be identified through the observation of superheated gas spiraling around them.

Before JWST, astronomers studied black holes using various space- and ground-based telescopes, which could only detect the brightest black holes, including those relatively close to Earth. JWST, on the other hand, is specifically designed to observe light from the distant Universe and is capable of detecting black holes lying much farther away, even those that were previously thought to be too faint to be detected.

In the Universe, distance can be measured by a parameter known as redshift, with higher values indicating greater distances and earlier appearances in the Universe’s history. Many of JWST’s recently discovered black holes have redshifts ranging from 4 to 6, corresponding to a time when the Universe was about 1 billion to 1.5 billion years old.

In JWST images, these faint black holes may appear as small and unimpressive blobs, but, as Jorryt Matthee, an astrophysicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, notes, “they are clearly different” from the surrounding galaxies.

JWST’s findings have revealed approximately ten times more faint black holes at these intermediate redshifts than previously known. The reasons for this abundance are not yet fully understood, as Kohei Inayoshi, an astrophysicist at Peking University in Beijing, admits, “we don’t understand yet.”

Additionally, JWST has achieved a significant breakthrough by detecting several of the most distant black holes ever observed. Among these is the confirmed record holder located at the heart of the well-studied galaxy GN-z11, boasting a redshift of 10.6. This suggests that black hole seeds had already formed and coalesced into supermassive objects as early as 400 million years after the Big Bang. Upcoming observations aim to explore the intricate details of the superheated gas flow around GN-z11, shedding light on how the black hole influences the surrounding space.

Furthermore, JWST spotted a potential black hole at a redshift of 8.7 in the galaxy CEERS 1019, which managed to accumulate a mass roughly 9 million times that of the Sun within the first 570 million years of the Universe. Moreover, there is even a candidate black hole at a redshift of 12.

These remarkable findings of distant black holes made by JWST align with recent simulations on the formation of early black holes. Raffaella Schneider, an astrophysicist at the Sapienza University of Rome, and her colleagues have discovered that significant black holes can form in the early Universe if they rapidly consume gas during their initial stages, surpassing the theoretical maximum rate at which black holes can grow. JWST’s observations suggest that some black holes, such as the one in GN-z11, might grow in this way, raising the possibility of revising the existing theory.

For Priyamvada Natarajan, an astrophysicist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, the excitement surrounding JWST’s black-hole discoveries has only just begun. She enthusiastically exclaims, “This is very early, quick stuff, with a lot more to come. It’s a dream. Honestly.”