Using the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope (VLT), astronomers have characterized a bright quasar, finding it to be not only the brightest of its kind but also the most luminous object ever observed. Quasars are the bright cores of distant galaxies, and supermassive black holes power them.

The black hole in this record-breaking quasar is growing in mass by the equivalent of one sun per day, making it the fastest-growing black hole to date.

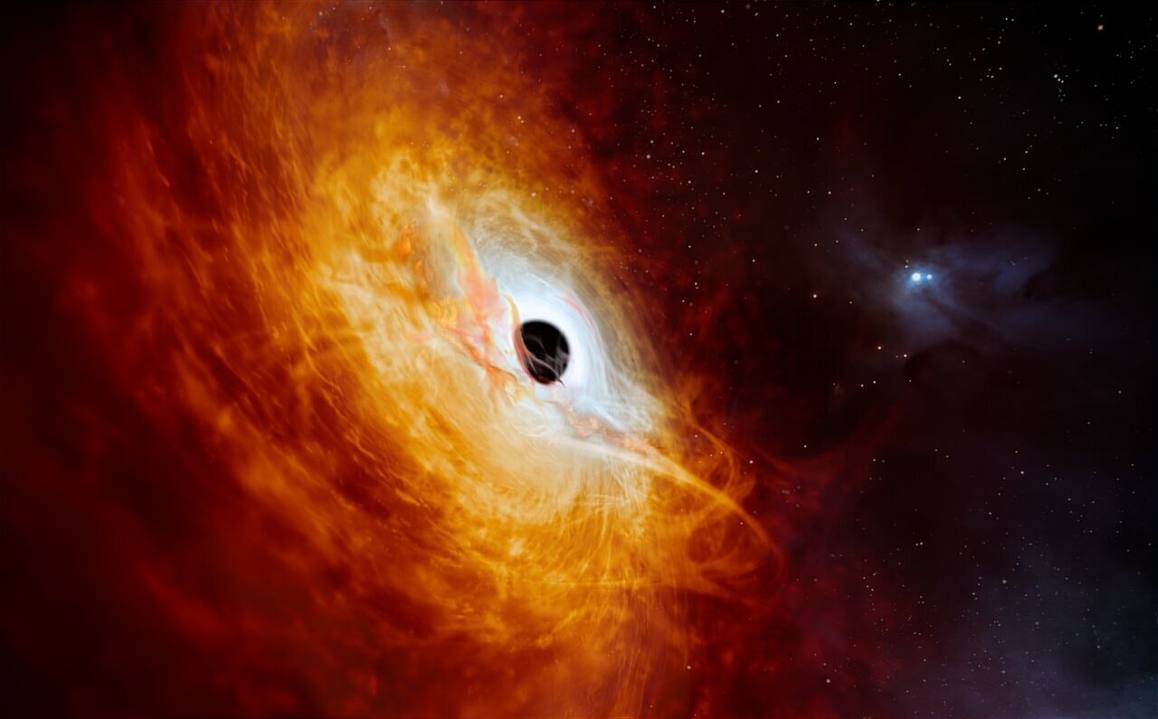

The black holes powering quasars collect matter from their surroundings in an energetic process that emits vast amounts of light. So much so that quasars are some of the brightest objects in our sky, meaning even distant ones are visible from Earth. Generally, the most luminous quasars indicate the fastest-growing supermassive black holes.

“We have discovered the fastest-growing black hole known to date. It has a mass of 17 billion suns and eats just over a sun per day. This makes it the most luminous object in the known universe,” says Christian Wolf, an astronomer at the Australian National University (ANU) and lead author of the study published Nature Astronomy. The quasar, called J0529-4351, is so far away from Earth that its light took over 12 billion years to reach us.

The matter being pulled in toward this black hole, in the form of a disk, emits so much energy that J0529-4351 is over 500 trillion times more luminous than the sun. “All this light comes from a hot accretion disk that measures seven light-years in diameter—this must be the largest accretion disk in the universe,” says ANU Ph.D. student and co-author Samuel Lai. Seven light-years is about 15,000 times the distance from the sun to the orbit of Neptune.

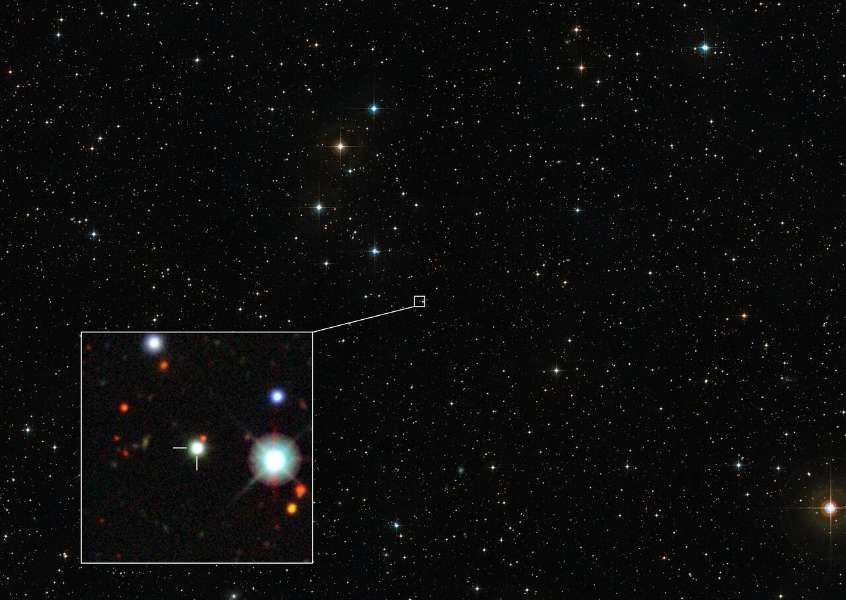

Remarkably, this record-breaking quasar was hiding in plain sight. “It is a surprise that it has remained unknown until today when we already know about a million less impressive quasars. It has been staring us in the face until now,” says co-author Christopher Onken, an astronomer at ANU. He added that this object showed up in images from the ESO Schmidt Southern Sky Survey dating back to 1980, but it was not recognized as a quasar until decades later.

Finding quasars requires precise observational data from large areas of the sky. The resulting datasets are so large that researchers often use machine-learning models to analyze them and tell quasars apart from other celestial objects.

However, these models are trained on existing data, which limits the potential candidates to objects similar to those already known. If a new quasar is more luminous than any other previously observed, the program might reject it and classify it instead as a star not too distant from Earth.

An automated analysis of data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite passed over J0529-4351 for being too bright to be a quasar, suggesting it to be a star instead. The researchers identified it as a distant quasar last year using observations from the ANU 2.3-meter telescope at the Siding Spring Observatory in Australia.

However, discovering that it was the most luminous quasar ever observed required a larger telescope and measurements from a more precise instrument. The X-shooter spectrograph on ESO’s VLT in the Chilean Atacama Desert provided crucial data.

The fastest-growing black hole ever observed will also be a perfect target for the GRAVITY+ upgrade on ESO’s VLT Interferometer (VLTI), which is designed to accurately measure the mass of black holes, including those far away from Earth.

Additionally, ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), a 39-meter telescope under construction in the Chilean Atacama Desert, will make identifying and characterizing such elusive objects even more feasible.

Finding and studying distant supermassive black holes could shed light on some of the mysteries of the early universe, including how they and their host galaxies formed and evolved. But that’s not the only reason why Wolf searches for them. “Personally, I simply like the chase,” he says. “For a few minutes a day, I get to feel like a child again, playing treasure hunt, and now I bring everything to the table that I have learned since.”

Reference:

Christian Wolf, The accretion of a solar mass per day by a 17-billion solar mass black hole, Nature Astronomy (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-024-02195-x.