Euclid’s two instruments have captured their first test images. The mesmerizing results indicate that the space telescope will achieve the scientific goals that it has been designed for—and possibly much more.

Although there are months to go before Euclid delivers its true new view of the cosmos, reaching this milestone means the scientists and engineers behind the mission are confident that the telescope and instruments are working well.

“After more than 11 years of designing and developing Euclid, it’s exhilarating and enormously emotional to see these first images,” says Euclid project manager Giuseppe Racca. “It’s even more incredible when we think that we see just a few galaxies here, produced with minimum system tuning. The fully calibrated Euclid will ultimately observe billions of galaxies to create the biggest ever 3D map of the sky.”

ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher congratulates the Euclid team: “It is fantastic to see the latest addition to ESA’s fleet of science missions already performing so well. I have full confidence that the team behind the mission will succeed in using Euclid to reveal so much about the 95% of the universe that we currently know so little about.”

Carole Mundell, ESA’s Director of Science agrees: “Our teams have worked tirelessly since the launch of Euclid on 1 July and these first engineering images give a tantalizing glimpse of the remarkable data we can expect from Euclid.”

Yannick Mellier, Euclid Consortium lead adds, “The outstanding first images obtained using Euclid’s visible and near-infrared instruments open a new era to observational cosmology and statistical astronomy. They mark the beginning of the quest for the very nature of dark energy, to be undertaken by the Euclid Consortium.”

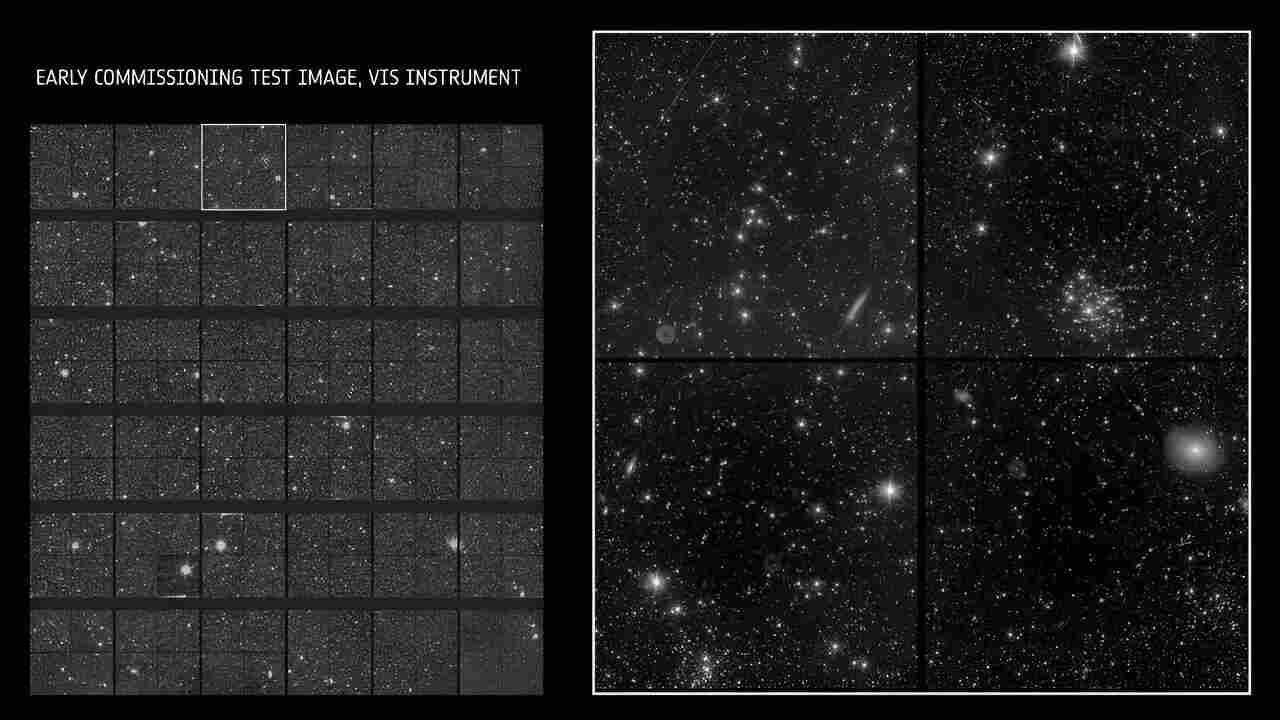

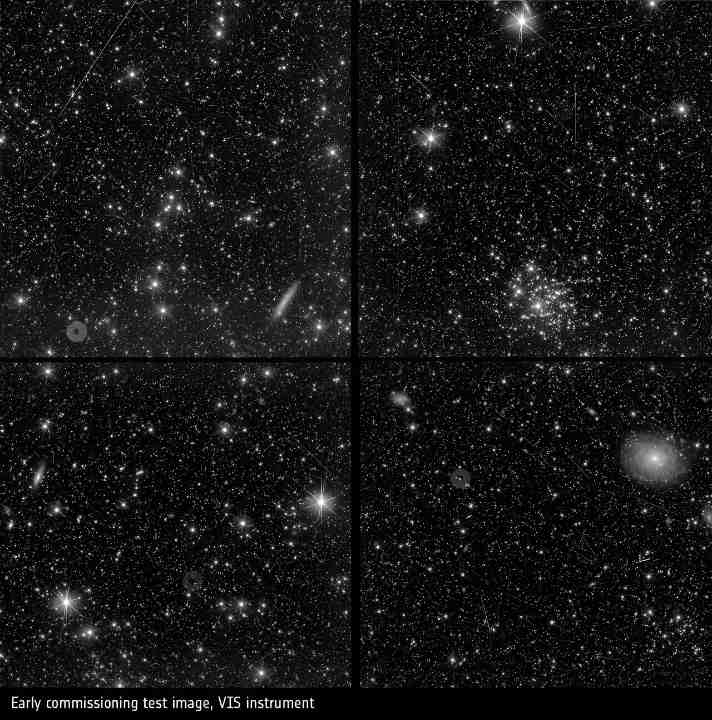

The universe in visible light

Euclid’s VISible instrument (VIS) will take super sharp images of billions of galaxies to measure their shapes. Looking closely at this first image, we already get a glimpse of the bounty that VIS will bring; while a few galaxies are very easy to spot, many more are fuzzy blobs hidden among the stars, waiting to be unveiled by Euclid in the future. Though the image is full of detail, the area of sky that it covers is actually only about a quarter of the width and height of the full moon.

Mark Cropper from University College London led the development of VIS: “I’m thrilled by the beauty of these images and the abundance of information contained within them. I’m so proud of what the VIS team has achieved and grateful to all of those who have enabled this capability. VIS images will be available for all to use, whether for scientific or other purposes. They will belong to everybody.”

Reiko Nakajima, VIS instrument scientist adds, “Ground-based tests do not give you images of galaxies or stellar clusters, but here they all are in this one field. It is beautiful to look at, and a joy to do so with the people we’ve worked together with for so long.”

The image is even more special considering that the Euclid team was given a scare when they first switched the instrument on: they picked up an unexpected pattern of light contaminating the images. Follow-up investigations indicated that some sunlight was creeping into the spacecraft, probably through a tiny gap; by turning Euclid the team realized that this light is only detected at specific orientations, so by avoiding certain angles VIS will be able to fulfill its mission. This image was taken at an orientation where the sunlight was not an issue.

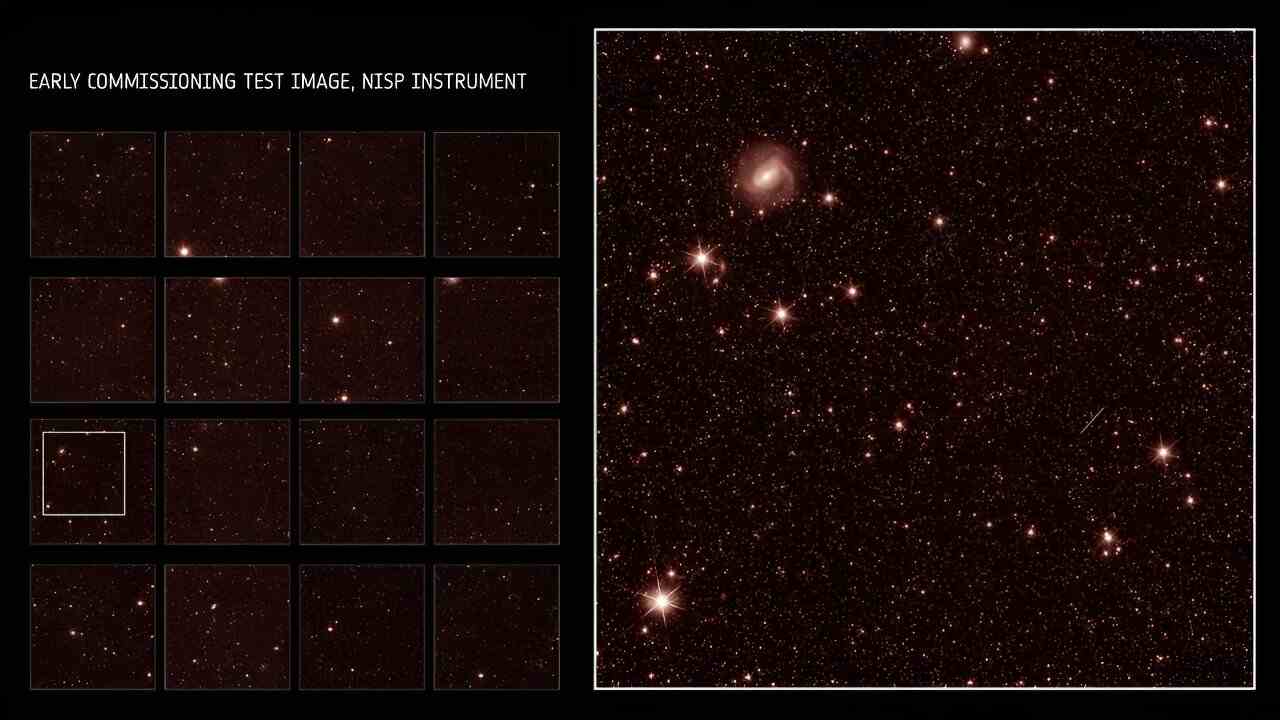

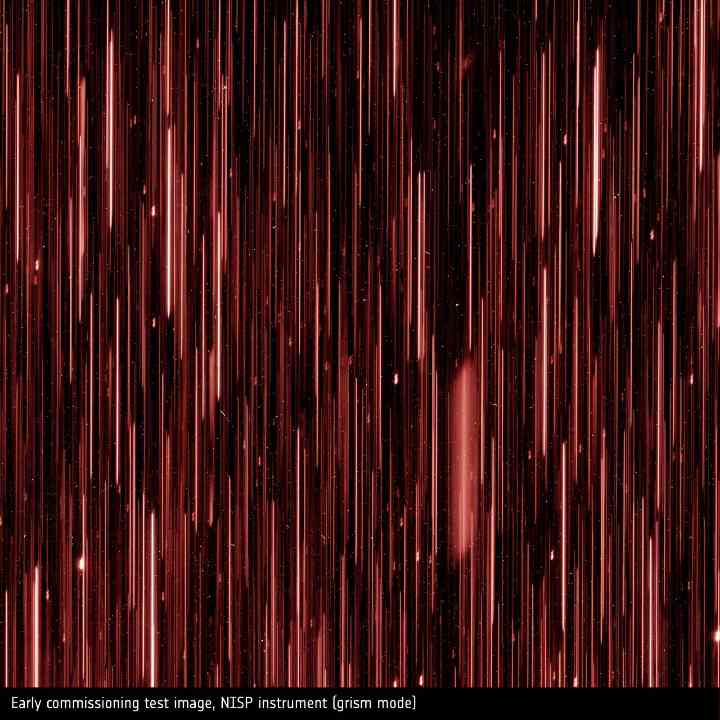

The universe in infrared light

Euclid’s Near-Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP) instrument has a double role: imaging galaxies in infrared light and measuring the amount of light that galaxies emit at various wavelengths. This second role lets us directly work out how far away each galaxy is.

By combining distance information with that on galaxy shapes measured by VIS, we will be able to map how galaxies are distributed throughout the universe, and how this distribution changes over time. Ultimately, this 3D map will teach us about dark matter and dark energy.

In the image below, before reaching the NISP detector the light from Euclid’s telescope has passed through a filter that measures the brightness at a specific infrared wavelength.

In this second image, the light from Euclid’s telescope had passed through a ‘grism’ before it reached the detector. This device splits light from every star and galaxy by wavelength, so each vertical streak of light in the image is one star or galaxy. This special way of looking at the universe allows us to determine what each galaxy is made of, which allows us to evaluate its distance from Earth.

NISP instrument scientist Knud Jahnke says, “We’ve seen simulated images, we’ve seen laboratory test images—it’s still hard for me to grasp these images are now the real universe. So detailed, just amazing.”

NISP instrument scientist William Gillard adds, “Each new image we uncover leaves me utterly amazed. And I admit that I enjoy listening to the expressions of awe from others in the room when they look at this data.”

On the road to science

It is worth noting once more that these snapshots—beautiful though they are—are still early test images, taken to check the instruments and review how the spacecraft can be further tweaked and refined. Because they are largely unprocessed, some unwanted artifacts remain—for example the cosmic rays that shoot straight across, seen especially in the VIS image. The Euclid Consortium will ultimately turn the longer-exposed survey observations into science-ready images that are artifact-free, more detailed, and razor sharp.

Over the next few months, ESA and industry colleagues will continue to carry out all the tests and checks needed to ensure that Euclid is working as well as possible. At the end of this ‘commissioning and performance verification phase’, the real science begins. At that point ESA will release a new set of images to demonstrate what the mission is capable of.